Speaking of cloud computing (see my previous, sponsored post), I will be celebrating my birthday on Sunday by attending an all-day UX conference at UX Salon in Tel Aviv, including evening cocktails on the rooftop of Wix at Tel Aviv harbor. Ok, that's not exactly cloud computing, but my company Ex Libris is sending me, and their platforms are heavily based on cloud computing.

Learning UX is parallel to, and integrated with, being a better technical writer, as I wrote in my presentation at MegaComm.

I feel that game design and gamification are opposites but parallels to UX design: game designers want you to spend more time with the product because they want you to find it entertaining or recreational, while UX designers and technical writers want you to spend less time with the product because they know that you're using the product in order to accomplish something else. A game should be involving and engaging; figuring out how to run the game or use the controller should not be, unless that's part of the entertainment.

Both of them carefully consider presentation and how to create a better user experience. I feel, after having been a game designer and having learned gamification, and now working for many years as a technical writer and starting to learn UX, that I am filling in my knowledge on both sides of the same coin.

Showing posts with label technical communication. Show all posts

Showing posts with label technical communication. Show all posts

Friday, April 01, 2016

Monday, March 07, 2016

Don't Be a Technical Writer, Be an Interface Designer

Here is my presentation at Megacomm February 2016, slide by slide, with my accompanying talk and some notes. I don't write down what I say on the slides, nor do I have a script, so the text is an approximation of what I said.

In this presentation, I propose the following two theories.

One: technical writers are actually interface designers. A good technical writer approaches his or her work as someone who designs an interface. A good technical writer is a good interface designer. Two: Since the core competency of a technical writer is designing an interface, technical writers have the core competency required for other interface design jobs, and should a) help their company in this capacity, or b) with some additional technical knowledge, consider alternative work doing other interface design jobs.

That's it, I'm done. Any questions?

Just kidding. Actually, I want to start with an old joke, so old that some of you may not know or remember it.

Two guys are in a two-seater airplane flying in Chicago. The pilot knows Chicago like the back of his hand, but there is a pea-soup fog and he can't see more than 10 feet out the window. The plane is almost out of fuel and the passenger is getting very worried. If they could only figure out where they are, the pilot could land the plane safely. Suddenly they pass a building on the left, and a man is standing at an open window. The pilot yells "Where are we?!" The man in the building yells back "You're in an airplane!" The pilot yells "Thanks", turns left, turns right, and lands at Chicago airport. The passenger is thrilled, but confused. He says "I'm so glad we were able to land safely, but how did that man's answer help you?" The pilot replies "Well, what he told me was technically accurate but completely useless, so it had to be the IBM documentation building.

The point of this presentation is to remind you that some people forget what the job of a technical writer is, and it's not to provide technically accurate information about a product. It's not to explain procedures or describe how the product works in detail. The job of a technical writer is help someone do something with your product because they have to use your product. They don't want to use it, and they don't want to use your documentation. They would rather be at the beach; using your product, especially if the product doesn't immediately communicate its function to them and they have to use your documentation, is not what the customer wants to be doing. Your job is to design a good interface. It is to help him or her get back to the beach. Of course, sometimes you have to provide technical information to do that, but if you have to you've already lost part of the battle.

But first, I will define what an interface is.

An interface is something that helps you use something to do something. The emphasis here is on "do something". You have no interest in the tool that you have to use to do the something, you just want to do the something. If you could think it and have it happen without having to use the tool, you would do that. But you can't; you have to use the tool. The interface is how you use that tool. For example.

Here is a mountain. The interface to the mountain is the mountain's surface, which is how you "use" the mountain. If you live on one side of the mountain and you want to shop at the grocery store on the other side, you use the mountain's surface to do that. You would like the mountain's interface to be as simple and straightforward as possible, because you don't really want to use the mountain; you have to use it to get to the other side.

Of course, there are people who actually like to use a mountain's interface; people who like to climb mountains. Some people use products for recreation or for entertainment; these products are designed for their interface; these people want to use the interface. These people enjoy the interface in its own right.

This talk is not about these kinds of people or these kinds of interfaces. For most of us, who are not making recreational or entertainment products, the interface is something that HAS to be used. Even if the product has a great feature that we want to use, we would prefer to just think what we want to have happen and have it happen. Since we can't, we HAVE to use the product to achieve the result. We want the interface that is required to achieve that result be as simple and as invisible as possible.

The challenge is that companies, and R and D departments in particular, design products and documentation that is the exact opposite of that: they design IBM documentation, under the belief that people WANT to use their product or read their documentation. That people want to spend their time learning things, and defining and managing and configuring things, just because that's what the inside or back-end of the product does. R and D departments are proud of their tools and they think about the ways that things are done internally in products, and then they want to communicate this to users: how the product works. They do this not only with documentation that is uninteresting to the users, but with the interfaces, asking you define profiles, and configure internal configuration parameters, asking you to learn new languages and terminology and acronyms in order to understand how the product operates. But people don't care about your products or how it operates; they just want to do their thing and get back to the beach. They don't want to learn, they want to know already.

Your job as a technical writer, just like the job of anyone designing the interface to your product, is to not teach the user a new language or have them think hard about how to work or manage the product, as far as possible.

What makes a good interface?

A good interface is invisible; it doesn't make you think. It is, as much as possible, an extension of the user's will to just think it and have it done. The more a user is thinking about your interface, the less good your interface is (unless the interface is, itself, entertaining).

A good interface is unsurprising; features and controls are where you would expect them and work how you expect them to work. If there is a back, there is a forward. If there is a left, there is a right. If the menu is scrolled using a finger flick in this area, then the menu is scrolled using a finger flick in every area. In this iPod, the sub-menu is going to look the same no matter which menu option I select, and the same command will return to the main menu from any sub-menu.

A product may be the best product in its class, offering the most features, but if the features are hard to find and difficult or even surprising and complex to use, the interface is not good. A good interface will always provide less options for easy to understand features, hiding the complexity as required. More features may make a better product, but don't always make a better interface.

A good interface doesn't ask you to learn a new language. It doesn't replace standard words - like dogs - with brand names - like BarkBuddies - forcing you to learn the terminology before you can use the interface or read the document. Your company may send acronyms back and forth in internal emails, but of course a good interface doesn't use these acronyms, making you learn the language in order to understand what is written. Don't make the user learn; inform them and let them forget.

A good interface exposes tasks, not tools. You use the product to do something, not learn about the product. In the iPod here, it could have said "Artists", "Albums", and "Genres", but it didn't. It says "Play this artist", "Play an album", "Get help", offering you the actions you want to take. If it just said "Artists", you wouldn't know if that's a tool to add an artist or view the artists, or what have you. Yeah, you could probably figure it out in a few seconds, but the interface doesn't make you do that. Help your users get back to the beach, get over the mountain, as quickly as possible.

Lastly, a good interface makes the customer feel that the time they spent using the product to do what they really wanted to do was worth it. If your mountain's surface is too hard to use, the user is going to find another way around the mountain or another grocery store. In the end, the user has to feel that the time and money spent were worth it.

Who designs interfaces? Or who is supposed to design interfaces, anyway?

Physical products, such as doors and chairs, have designers - sometimes good and sometimes bad. Apple, of course, puts a lot of thought into the design of their interface. In most tech companies, whether they produce hardware or software products, the designer is typically a product manager. The problem with the product manager is that most of them don't know much about product design. They are skilled at talking to customers, deciding on features, making specifications and time charts and budgets and so on, but they don't understand design - even though it's one of their jobs. And they don't always know that they don't know it.

Of course, technical documentation is done by a technical writer, who is really making an interface, so there's her. And your company may have other, actual interface designers, like a UX designer or product designer. A UI designer is the one who makes pretty flash screens for your web sites, and they are supposed to be good at UX (user experience) design, but they tend to suck at it, as you can see by visiting any bank website in Israel: every one of them has a long loading flash screen that blocks the site and hover-happy menus that cover the entire page when you try to navigate. That's not thinking about the user experience, that's being in love with your programming toolbox. A UX designer does actual interface design from the user's experience, and that's what I'm talking about. A good technical writer has a good start for learning to be a UX designer, since they share the same core skills and perspective.

Why are product managers and development teams bad at design? Because they are in love with and proud of their products, which is fine. But then they want to communicate all about these products to the customers, whether by means of a fancy over-communicative interface or a ton of useless technical documentation.

As an example, here is the "K Key" story: I received a page and a half from a developer to document ("just fix the English!" he cheerfully told me). It read: when the user presses the "k" key, the key presses a spring that hits a contact, the contact sends a burst of electricity over the chipboard to a multiplexer/demultiplexer, which translates the signals into hexadecimal blah blah and so on for a page and a half until finally a "k" appears on the screen. After looking at this for a few minutes, I realized that the only thing I had to write was "Press the 'k' key to continue".

And even that was too much really, because the product should have been designed to not need this documented; in fact, it could have been designed to not need the "k" key pressed at all. It should just have continued to the next page. The only reason it didn't was because R and D had developed it to stop at that point during testing, and they figured that that's good enough for the customer.

Product creators love their products, god bless them. But what the customers need is an interface that lets them cross that mountain/get back to the beach as quickly as possible. I'm sorry it took you four months to develop a working "k" key, and I'm really happy that it works so well, but that doesn't meant that we have to make the customer aware of that process.

Product managers typically care only that the product works. So if this API uses one set of parameters and that API uses a different set of parameters, who cares? It works. How did this happen? This one was developed by Itzik and that one was developed by Galit. The product manager should care, because the customer is going to have to use both APIs and he doesn't want to learn a new set of parameters with every new API. "It works" isn't good enough.

It turns out that there is this hole in development, that in theory is filled by a product manager or developer, but in practice it isn't. It's a hole that happens to be exactly what a good technical writer does. Development has the programming skills to develop and the product manager is good at creating user stories, but they are missing the ability to design a product that is simple and invisible for the user. This is a hole that a technical writer can fill, but not if she is at the end of the development process, handed a working product and told to document it. By then it is too late.

After the design is done, a technical write can complain about the product design, but - at best - that becomes a bug to fix in some later development cycle that is at least two months away. And the problem with an interface, particularly an API, is that once it is in use it becomes very hard to change. So the fix never happens.

Technical writing should be sitting in the design review meetings. With their overall view of the product (having documented the entire product), they can ask why this feature doesn't work the same way as the other feature that was designed last month, or why this screen uses a different methodology for entering input than the other screen that was just documented. They can feel out the flow of the product, and find ways to make the experience less bumpy for the user.

To do this, you have to be a good technical writer, who thinks about interfaces. You have to have a good overview of the product's entire interface, one that the product manager(s) doesn't. And you should have some basic technical skills, enough to understand how methods and web sites work (or whatever your company is using as an interface).

Why should you do this? Because it makes a better product. It increases your value to your company, and makes you more than just a technical writer. It makes you more integrated with and more respected by the development team. And, the more you develop a general skill at designing interfaces, the more able you are to switch to a different kind of interface design job, should you eventually choose to do so.

I did a presentation on proper API design. For now, I'll just cover the basics about why a good technical writer already has many of the skills necessary to be a good interface designer, even without too much technical knowledge.

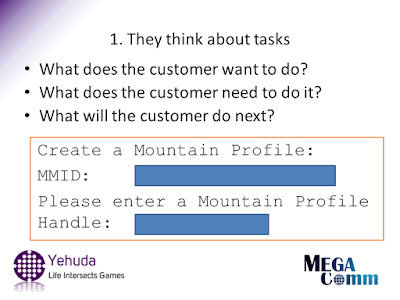

A good technical writer thinks about what the customer wants to do, not how to describe the tools. He uses action verbs. He ensures that the customer has all of the information he needs to do that task, and then considers what the customer wants to do next, until he is done. In other words, he thinks "How do I get the customer out of this documentation as soon as possible and back to the beach?"

In contrast, bad technical writers and bad designers think the customer wants to spend time learning and figuring out your wonderful site. The above slide presents a UI for using the mountain, like many bad UIs I have had to document. What is a mountain profile and why should I have to learn that? What is an MMID? How do I find it? Why do I need to define three different IDs for what I'm trying to do? In fact, why do I have to define any? Is this helping me get to the other side of the mountain? Can't all of this be created internally without my having to learn what it all means? Of course it can, and it should. What we have here is a development team in love with its programming methodology. The program uses profiles internally; that doesn't mean that the user should have input fields that match the internal descriptions one for one. The development team has been programming this for 2 years, so they know what an MMID is (they usually just enter 1234). But the customer doesn't, and doesn't need to. The acronym should be spelled out, and the term either hidden or pre-filled, or a link added to navigate to the screen that gives you your ID. As a good technical writer, you already know that.

Technical writers know to use less words, present only relevant concepts, and don't abbreviate terms. They present what is required, and no more than what is required. This same skill is necessary for any type of interface.

A good technical writer ensures that information is not ambiguous. You don't write "x may be created", because the reader doesn't know if the system might create x or the user is now allowed to create x. Similarly, the technical writer knows, without much technical skill, that an API like DogBarks is ambiguous. Does it mean that the dog is able to bark, or does it mean that the dog has just barked? Verbs indicate actions, and nouns indicate states. A good technical writer can help with the API names, as well as the parameter and value names, even with little technical skill.

A good technical writer thinks about consistency. Especially in Israel, technical writers can review the interface's field names and parameter names for spelling mistakes, and ensure that case is used consistently across the product. Why would it be inconsistent? Because Itzik programmed this API and Dalit programmed that one, and the product manager didn't care because they worked. Similarly, just like information in documentation should be presented in an easy to navigate, consistent manner, a good API uses the same parameter names to mean the same things and orders the parameters in the same ways in each command. Or displays the fields in the same way on different pages.

These are just examples; I cut out many other examples owing to time.

If you want to joint the development team, interface design is a great start, but you will be more effective with language or technological skills in the areas that your development team works. If you

want to move to another profession, like UX design, the core skill is a great start, but you still need to learn more about the other professions and what skill sets they require. The transition will be easier, because the core focus is similar in technical writing and the other profession.

To conclude: A good technical writer is a good interface designer, because that is the job of documentation. And a good interface designer can contribute his or her skills to other areas of the product, and can consider moving toward another profession that requires similar skills.

Thank you.

Yehuda

One: technical writers are actually interface designers. A good technical writer approaches his or her work as someone who designs an interface. A good technical writer is a good interface designer. Two: Since the core competency of a technical writer is designing an interface, technical writers have the core competency required for other interface design jobs, and should a) help their company in this capacity, or b) with some additional technical knowledge, consider alternative work doing other interface design jobs.

That's it, I'm done. Any questions?

Just kidding. Actually, I want to start with an old joke, so old that some of you may not know or remember it.

Two guys are in a two-seater airplane flying in Chicago. The pilot knows Chicago like the back of his hand, but there is a pea-soup fog and he can't see more than 10 feet out the window. The plane is almost out of fuel and the passenger is getting very worried. If they could only figure out where they are, the pilot could land the plane safely. Suddenly they pass a building on the left, and a man is standing at an open window. The pilot yells "Where are we?!" The man in the building yells back "You're in an airplane!" The pilot yells "Thanks", turns left, turns right, and lands at Chicago airport. The passenger is thrilled, but confused. He says "I'm so glad we were able to land safely, but how did that man's answer help you?" The pilot replies "Well, what he told me was technically accurate but completely useless, so it had to be the IBM documentation building.

The point of this presentation is to remind you that some people forget what the job of a technical writer is, and it's not to provide technically accurate information about a product. It's not to explain procedures or describe how the product works in detail. The job of a technical writer is help someone do something with your product because they have to use your product. They don't want to use it, and they don't want to use your documentation. They would rather be at the beach; using your product, especially if the product doesn't immediately communicate its function to them and they have to use your documentation, is not what the customer wants to be doing. Your job is to design a good interface. It is to help him or her get back to the beach. Of course, sometimes you have to provide technical information to do that, but if you have to you've already lost part of the battle.

But first, I will define what an interface is.

An interface is something that helps you use something to do something. The emphasis here is on "do something". You have no interest in the tool that you have to use to do the something, you just want to do the something. If you could think it and have it happen without having to use the tool, you would do that. But you can't; you have to use the tool. The interface is how you use that tool. For example.

Here is a mountain. The interface to the mountain is the mountain's surface, which is how you "use" the mountain. If you live on one side of the mountain and you want to shop at the grocery store on the other side, you use the mountain's surface to do that. You would like the mountain's interface to be as simple and straightforward as possible, because you don't really want to use the mountain; you have to use it to get to the other side.

Of course, there are people who actually like to use a mountain's interface; people who like to climb mountains. Some people use products for recreation or for entertainment; these products are designed for their interface; these people want to use the interface. These people enjoy the interface in its own right.

This talk is not about these kinds of people or these kinds of interfaces. For most of us, who are not making recreational or entertainment products, the interface is something that HAS to be used. Even if the product has a great feature that we want to use, we would prefer to just think what we want to have happen and have it happen. Since we can't, we HAVE to use the product to achieve the result. We want the interface that is required to achieve that result be as simple and as invisible as possible.

The challenge is that companies, and R and D departments in particular, design products and documentation that is the exact opposite of that: they design IBM documentation, under the belief that people WANT to use their product or read their documentation. That people want to spend their time learning things, and defining and managing and configuring things, just because that's what the inside or back-end of the product does. R and D departments are proud of their tools and they think about the ways that things are done internally in products, and then they want to communicate this to users: how the product works. They do this not only with documentation that is uninteresting to the users, but with the interfaces, asking you define profiles, and configure internal configuration parameters, asking you to learn new languages and terminology and acronyms in order to understand how the product operates. But people don't care about your products or how it operates; they just want to do their thing and get back to the beach. They don't want to learn, they want to know already.

Your job as a technical writer, just like the job of anyone designing the interface to your product, is to not teach the user a new language or have them think hard about how to work or manage the product, as far as possible.

What makes a good interface?

A good interface is invisible; it doesn't make you think. It is, as much as possible, an extension of the user's will to just think it and have it done. The more a user is thinking about your interface, the less good your interface is (unless the interface is, itself, entertaining).

A good interface is unsurprising; features and controls are where you would expect them and work how you expect them to work. If there is a back, there is a forward. If there is a left, there is a right. If the menu is scrolled using a finger flick in this area, then the menu is scrolled using a finger flick in every area. In this iPod, the sub-menu is going to look the same no matter which menu option I select, and the same command will return to the main menu from any sub-menu.

A product may be the best product in its class, offering the most features, but if the features are hard to find and difficult or even surprising and complex to use, the interface is not good. A good interface will always provide less options for easy to understand features, hiding the complexity as required. More features may make a better product, but don't always make a better interface.

A good interface doesn't ask you to learn a new language. It doesn't replace standard words - like dogs - with brand names - like BarkBuddies - forcing you to learn the terminology before you can use the interface or read the document. Your company may send acronyms back and forth in internal emails, but of course a good interface doesn't use these acronyms, making you learn the language in order to understand what is written. Don't make the user learn; inform them and let them forget.

A good interface exposes tasks, not tools. You use the product to do something, not learn about the product. In the iPod here, it could have said "Artists", "Albums", and "Genres", but it didn't. It says "Play this artist", "Play an album", "Get help", offering you the actions you want to take. If it just said "Artists", you wouldn't know if that's a tool to add an artist or view the artists, or what have you. Yeah, you could probably figure it out in a few seconds, but the interface doesn't make you do that. Help your users get back to the beach, get over the mountain, as quickly as possible.

Lastly, a good interface makes the customer feel that the time they spent using the product to do what they really wanted to do was worth it. If your mountain's surface is too hard to use, the user is going to find another way around the mountain or another grocery store. In the end, the user has to feel that the time and money spent were worth it.

Who designs interfaces? Or who is supposed to design interfaces, anyway?

Physical products, such as doors and chairs, have designers - sometimes good and sometimes bad. Apple, of course, puts a lot of thought into the design of their interface. In most tech companies, whether they produce hardware or software products, the designer is typically a product manager. The problem with the product manager is that most of them don't know much about product design. They are skilled at talking to customers, deciding on features, making specifications and time charts and budgets and so on, but they don't understand design - even though it's one of their jobs. And they don't always know that they don't know it.

Of course, technical documentation is done by a technical writer, who is really making an interface, so there's her. And your company may have other, actual interface designers, like a UX designer or product designer. A UI designer is the one who makes pretty flash screens for your web sites, and they are supposed to be good at UX (user experience) design, but they tend to suck at it, as you can see by visiting any bank website in Israel: every one of them has a long loading flash screen that blocks the site and hover-happy menus that cover the entire page when you try to navigate. That's not thinking about the user experience, that's being in love with your programming toolbox. A UX designer does actual interface design from the user's experience, and that's what I'm talking about. A good technical writer has a good start for learning to be a UX designer, since they share the same core skills and perspective.

Why are product managers and development teams bad at design? Because they are in love with and proud of their products, which is fine. But then they want to communicate all about these products to the customers, whether by means of a fancy over-communicative interface or a ton of useless technical documentation.

As an example, here is the "K Key" story: I received a page and a half from a developer to document ("just fix the English!" he cheerfully told me). It read: when the user presses the "k" key, the key presses a spring that hits a contact, the contact sends a burst of electricity over the chipboard to a multiplexer/demultiplexer, which translates the signals into hexadecimal blah blah and so on for a page and a half until finally a "k" appears on the screen. After looking at this for a few minutes, I realized that the only thing I had to write was "Press the 'k' key to continue".

And even that was too much really, because the product should have been designed to not need this documented; in fact, it could have been designed to not need the "k" key pressed at all. It should just have continued to the next page. The only reason it didn't was because R and D had developed it to stop at that point during testing, and they figured that that's good enough for the customer.

Product creators love their products, god bless them. But what the customers need is an interface that lets them cross that mountain/get back to the beach as quickly as possible. I'm sorry it took you four months to develop a working "k" key, and I'm really happy that it works so well, but that doesn't meant that we have to make the customer aware of that process.

Product managers typically care only that the product works. So if this API uses one set of parameters and that API uses a different set of parameters, who cares? It works. How did this happen? This one was developed by Itzik and that one was developed by Galit. The product manager should care, because the customer is going to have to use both APIs and he doesn't want to learn a new set of parameters with every new API. "It works" isn't good enough.

It turns out that there is this hole in development, that in theory is filled by a product manager or developer, but in practice it isn't. It's a hole that happens to be exactly what a good technical writer does. Development has the programming skills to develop and the product manager is good at creating user stories, but they are missing the ability to design a product that is simple and invisible for the user. This is a hole that a technical writer can fill, but not if she is at the end of the development process, handed a working product and told to document it. By then it is too late.

After the design is done, a technical write can complain about the product design, but - at best - that becomes a bug to fix in some later development cycle that is at least two months away. And the problem with an interface, particularly an API, is that once it is in use it becomes very hard to change. So the fix never happens.

Technical writing should be sitting in the design review meetings. With their overall view of the product (having documented the entire product), they can ask why this feature doesn't work the same way as the other feature that was designed last month, or why this screen uses a different methodology for entering input than the other screen that was just documented. They can feel out the flow of the product, and find ways to make the experience less bumpy for the user.

To do this, you have to be a good technical writer, who thinks about interfaces. You have to have a good overview of the product's entire interface, one that the product manager(s) doesn't. And you should have some basic technical skills, enough to understand how methods and web sites work (or whatever your company is using as an interface).

Why should you do this? Because it makes a better product. It increases your value to your company, and makes you more than just a technical writer. It makes you more integrated with and more respected by the development team. And, the more you develop a general skill at designing interfaces, the more able you are to switch to a different kind of interface design job, should you eventually choose to do so.

I did a presentation on proper API design. For now, I'll just cover the basics about why a good technical writer already has many of the skills necessary to be a good interface designer, even without too much technical knowledge.

A good technical writer thinks about what the customer wants to do, not how to describe the tools. He uses action verbs. He ensures that the customer has all of the information he needs to do that task, and then considers what the customer wants to do next, until he is done. In other words, he thinks "How do I get the customer out of this documentation as soon as possible and back to the beach?"

In contrast, bad technical writers and bad designers think the customer wants to spend time learning and figuring out your wonderful site. The above slide presents a UI for using the mountain, like many bad UIs I have had to document. What is a mountain profile and why should I have to learn that? What is an MMID? How do I find it? Why do I need to define three different IDs for what I'm trying to do? In fact, why do I have to define any? Is this helping me get to the other side of the mountain? Can't all of this be created internally without my having to learn what it all means? Of course it can, and it should. What we have here is a development team in love with its programming methodology. The program uses profiles internally; that doesn't mean that the user should have input fields that match the internal descriptions one for one. The development team has been programming this for 2 years, so they know what an MMID is (they usually just enter 1234). But the customer doesn't, and doesn't need to. The acronym should be spelled out, and the term either hidden or pre-filled, or a link added to navigate to the screen that gives you your ID. As a good technical writer, you already know that.

Technical writers know to use less words, present only relevant concepts, and don't abbreviate terms. They present what is required, and no more than what is required. This same skill is necessary for any type of interface.

A good technical writer ensures that information is not ambiguous. You don't write "x may be created", because the reader doesn't know if the system might create x or the user is now allowed to create x. Similarly, the technical writer knows, without much technical skill, that an API like DogBarks is ambiguous. Does it mean that the dog is able to bark, or does it mean that the dog has just barked? Verbs indicate actions, and nouns indicate states. A good technical writer can help with the API names, as well as the parameter and value names, even with little technical skill.

A good technical writer thinks about consistency. Especially in Israel, technical writers can review the interface's field names and parameter names for spelling mistakes, and ensure that case is used consistently across the product. Why would it be inconsistent? Because Itzik programmed this API and Dalit programmed that one, and the product manager didn't care because they worked. Similarly, just like information in documentation should be presented in an easy to navigate, consistent manner, a good API uses the same parameter names to mean the same things and orders the parameters in the same ways in each command. Or displays the fields in the same way on different pages.

These are just examples; I cut out many other examples owing to time.

If you want to joint the development team, interface design is a great start, but you will be more effective with language or technological skills in the areas that your development team works. If you

want to move to another profession, like UX design, the core skill is a great start, but you still need to learn more about the other professions and what skill sets they require. The transition will be easier, because the core focus is similar in technical writing and the other profession.

To conclude: A good technical writer is a good interface designer, because that is the job of documentation. And a good interface designer can contribute his or her skills to other areas of the product, and can consider moving toward another profession that requires similar skills.

Thank you.

Yehuda

Tuesday, March 17, 2015

20 API Design Tips to Stop Annoying Developers

Here is my presentation at DevConTLV March 2015, slide by slide, with my accompanying talk and some notes. I don't write down what I say on the slides, not do I have a script, so the text is an approximation.

Don't name your APIs with names that have ambiguous meanings. English can be tricky; if you're not a native English speaker, get one to help you review your function and parameters names.

What's confusing here? "Barks" can mean "This animal can bark" or "This animal just barked". If a developer sees this, he or she can't tell which one you mean just by looking at it. Try one of the following.

Essentially, the developers had drifted part of the business logic to the application, instead of keeping it in the API where it belonged. As a result, you had an API that could not be called, let alone documented, because it didn't have access to information that was inside the API.

This talk was supposed to be 20 tips to stop annoying developers, but I stopped counting at 20. You're welcome to count along with the presentation and tell me how many there are at the end.

Every example in this presentation represents an actual example I've seen while documenting APIs.

Just to clarify, the title of this presentation means tips to "stop doing things that annoy developers", not "stop developers who are annoying". Which brings me to my first tip ...

What's confusing here? "Barks" can mean "This animal can bark" or "This animal just barked". If a developer sees this, he or she can't tell which one you mean just by looking at it. Try one of the following.

Now the action can't be misunderstood. However, ambiguity is just the start.

Take a look at the first one, "can_bark". This turned out to be a problem for me when I was documenting an API.

Typically, there are two types of APIs. In the first type, all of the business logic is in the API. In this case, the application acts as a funnel, sending information to the API and passing requests from the API back out. The application is notified about things that happened on the server, or by the user, or on the device, or in another application, or even another part of the application, and sends the information to the API. In turn, the API sends things back to the application and the application sends it back back out to the world. For this type of API, the application isn't supposed to think.

My documentation was supposed to say when to call each API function, and what to do with the information sent back from the API. The developers included a sample application that had this API "can_bark" in it. I asked the developers "When does the application call this?" They said "When the API is waiting for it". But when is that? Just look in the sample application. That's not the point, I said. The application isn't supposed to have business logic in it. The application can't know when to call anything; it just responds to external requests. If it has to decide on its own, I need to write a whole new document on how to design the application's business logic.

This API would have been fine if it responded to an event or call of some kind from the API itself. In other words, it didn't have to think for itself if it just responded to a request from an external source (the API) as usual, sending the requested information back to the external source.

(Another situation arose when new information arrived about an animal ("this dog can bark") to be sent to the API. The information could be sent using an API that already existed "animalUpdate", which meant that the new API wasn't required.)

The moral of the story is: don't split your business logic. If you use the kind of API that has all the business logic, keep the business logic in the API.

Another kind of API has none of the business logic and simply responds to requests from the application. For example, a device driver writes what the application tells it to write and reads what the application tells it to read. If you drift application business logic into this API, your next customer is going to want something different from it and you're going to have to redesign the API. So don't split your business logic.

This is me. I worked for 14 years as a system administrator and a web programmer, until I switched to technical writing over ten years ago. Between my roles as technical writer, teacher of game rules, and now a designer of APIs, one of my major skills is to turn complicated ideas or topics into very simple ones. I teach complicated games so that they can be understood in only a few minutes, take 200 page documents and turn them into 120 page documents, and take 60 page documents and turn them into 2 page tech sheets.

I have documented dozens of APIs. When I get an API to document that is overly complicated, or would require a lot of documentation (and therefore a lot of work for the integrator to understand) because it doesn't match the rest of the APIs, I go back to the developers and say, hey, rather than write complicated documentation, let's rewrite the API. That gets me into trouble with some developers, but the product managers are generally happy. The result, in some of the places that I worked, was that API functions, names, parameters, and so on went through me before they were implemented. I sat in the design process.

Which makes sense. It's not enough for a web site to work. Nowadays you hire a UX designer to ensure that your web interfaces are clean and neat and don't drive away potential users. The same should be true for your APIs. It's not enough to say "they work!" If they are complicated, ugly, or difficult to integrate, you may drive away potential integrators.

In this talk I'm first going to talk about what makes a good API in general. Then I'll give some general tips for APIs, then some specific tips for specific instances, like actions and parameters. I'll end with general tips about documentation and delivery.

What is the object of an API?

It's the same object as your UI or your product: help your customers to be awesome. (Note that I stole this idea from a fantastic lady and speaker, Kathy Sierra.) The ultimate object is not to have an awesome product. Your product should be awesome, of course, and you can sell that in your marketing documentation. But no one wants to use your API, or read your document, or even use your product (unless it's a status symbol). They use it because they have to in order to be awesome, to do what they really want to do.

People buy a cool bicycle because it has a tungsten carbide frame, cool anti-rust paint, blah blah. But then they have to use the bike - interface with it - and they don't want to spend time trying figure out your fancy features, If the interface isn't "get on the bike and push the pedals", it means that they have to read the manual.

"Have to" is not a Good Thing. People "have to" use your APIs or "have to" read your documentation. No one "wants to" do these things (unless you're a hacker who loves systems, like me), so it's a negative experience. They do them because they have to. If they can do it easier using someone else's product, they will. If they have to use yours because you have a monopoly on some kind of feature, they will; you have them over a barrel. But you're not going to make any friends by forcing someone to do something that they "have to" do.

The object of any API is the same as the object of a technical document: to have the user/reader use it as little as possible. Ideally, not at all. If they have to use it, You've already lost something. Make it as simple, quick, and painless as possible for the user to get in and get out.

Your job in writing an API is not to sell your technology. You should not write an API that goes "start the super cool dog grooming feature". The API should be "groom the dog". Keep focus on what the user wants to do, not on what a great feature you're providing. Otherwise, your API will be bloated and loaded with all kinds of things that you think are cool but are forcing users to learn your language, showing off features that are not helping them get in and out as fast as possible. Obviously, if a user has to use a feature, you have to provide a way for him or her to use it. But keep the focus on the user, not the technology.

(Here's another slide totally stolen from Kathy Sierra.) On the left is what you promise your customer. She's going to take a cool picture while climbing a mountain. It's going to be awesome. On the right is what you deliver to the customer: technological documentation and interfaces in love with themselves, all of which she has to wade through to get to the cool picture on the left. Again, some of this is inevitable; you have to describe how the camera really works. But keep the gap as small as possible. Focus on getting the user in and out of your API as fast as possible so they can get to being cool.

So what makes a good API?

A good API (or document) is invisible. The customer doesn't feel it or see it any more than they have to. It is so natural that it doesn't feel like they are learning or using it.

A good API (or document) is unsurprising. If there's a left, there's a right. If there's an up there's a down. If it works one way here it works the same way there. It works the way every other API works. The user doesn't have to know something different to use every functions. It works exactly as expected, so that it needs no (or almost no) documentation.

An API that presents a few good features well, unsurprising, and easy to implement is better than one with lots of complicated features that have to be learned one at a time. Complicated, hard to understand and hard to implement. It may be inevitable that you have to provide something bad or complicated for a feature that the user MUST use, but minimize this as much as possible.

In the end, an API is good when the user feels that the money he or she spent on the product was worth it.

Have someone constantly looking it over to ensure that it's all consistent and logical, even if you are working in agile. Agile development adds features here and there as they come up without worrying about how they fit together as a whole. Ronit on Inbal's team added this feature, and Itzik on Moshe's team added that feature, and they all work, so done, right? No. Ronit used one kind of parameter set and Itzik used a different kind, and now the integrator has to learn two different methodologies to integrate them, which is annoying.

Keep a master plan for your actions, objects, parameters, and values, and keep it up to date with each new addition and each release.

Because it's very hard to change an API after it's released. If your code has mistakes and discrepancies that are hidden from the user inside the code, I don't care. You can release new code and fix it. When an API is released and customers are using it, it's painful and annoying to have to rewire an applications to incorporate the new API. It's worthwhile getting the API right the first time.

How do you write a good API? Think like a customer. A customer thinks: what do I want to do? Give the customer use-cases that show what your API does, and give him APIs that do things, with useful verbs.

An R&D team has access to all kinds of dummy information at all times. They forget that, in the real world, the integrator starts with nothing. If your API takes the list of dog breeds as input, where does the customer get that list of breeds? From this other API, that requires the list of dogs. Where do they get the list of dogs? From this other API that requires the list of kennels ... It's ok to cascade API requests, just make sure the developer can easily find the input for every API.

Then make sure they can use the results you send back to them as the input for the next API. Don't send back dog names in one API and ask them for dog IDs in the next. Unless the returned information is heading straight to a UI screen or a log file, your user is not a person, it's an application; it needs to feed the results of one request into the next.

How do you end up with this, where one function is camel case and one has underscores? Well, Ronit on Inbal's team added one feature, and Itzik on Moshe's team added the other feature. "It works!" But it's annoying. Don't do it.

Same thing for the parameter order and what gets passed. The first function takes a pointer, the second takes the variable followed by a Boolean, and the third takes the Boolean followed by a literal. How did this happen? Ronit on Inbal's team added the first one and ...

Here dogs are defined by a flat set of fields with feet and so on. But cows has a two-level structure of fields with limbs, followed by feet and hands. Be consistent in how you construct your data structures.

If a name or a term appears somewhere it should mean the same thing everywhere, and the terms you use for one thing should be the same for everything. Your pet store started with only dogs, and the names used "name". They added cats, and now they use "catName". Please. Also, "bark" means one thing, for dogs yes or no, but "bark" is the same word but has a different meaning, an enumeration, when used for trees. Be consistent.

Shorter is nearly always better. Shorter words are clearer and more logical. I know you want to be helpful by adding "is" and phrases and so on like this, but it's more to read for the user and not any more clear. In this case, the test "is this an animal" is always going to appear in an "if" clause, and it reads cleaner by just using the noun "animal", which means yes or no.

But there is a limit to being short. Don't abbreviate English words. Aside from being hard to read, you might run into abbreviations that can mean more than one word. I keep running into abbreviations or acronyms used by non-native English speakers that have unintentional vulgar or ridiculous meanings.

Here the type is "dog" but the user still has to define all of these other things, like the number of "legs" and the sound a dog makes, when these should be defaults. Use defaults.

Your company decided to rebrand. From now on dogs will be "BarkBuddies". That's fine, and the new APIs use BarkBuddies, but all the old ones still use dog. Don't do that. Yes, it's a pain to have your customers move to a brand new version of the API, but that's still better than an API that uses several types of terminology for the same thing. It starts with just a few functions but it always ends up as a mess.

Get someone to review your function names, parameter names, and so on BEFORE you implement them, not a week before delivery when your R&D team is too busy to revamp all of the code to fix problems. Because they won't. They'll say they'll fix it in the next release, but by then it will be too hard and too late, and they'll be working on new features.

In my jobs, new functions went through technical writing, but it could just as easily go through QA or support, as long as it goes through someone who writes English well and will push back and ask for changes.

And of course, make sure it really does work. An API with functions that don't actually work is annoying, too.

Here are some more specific tips.

Use a consistent naming structure for your actions. For instance, if you add a new animal, always use "add". Or "create" or "set", whatever you choose, just always make it the same. One popular method is "CRUD" which stands for create, read, update, delete. I like to use "set" and "get" because it's short and sweet. But it doesn't matter, as long as the same thing always uses the same word.

If you're using a REST API, make sure your REST commands match your actions. Don't use POST for edit or delete, or PUT for read.

Here you create an animal using a single command, but you edit each animal using multiple commands. Why? Because Itzik from Eyal's team programmed ... Here you update each item in a dog using a different command, but edit the same things in a cat using one command for everything. Don't do that.

Verbs set, nouns get. ParagraphCapital does not make the first letter of a paragraph capital, it checks if the paragraph is capitalized. Use a verb to set the paragraph. More simply, you set a state using setState, you get the state using state or getState.

Please avoid using Booleans, because they will always, always, (almost) always change to non-Booleans in the next version. You started the pet store with dogs. Then you added cats, so some developer added isDog to some commands. But other APIs defaulted to dog, so she used isNotDog. And then elsewhere she used isCat, just to mix it up a little.

Then you start selling elephants, snakes, giraffes, turtles, and fish. How many Booleans do you need to add now? Just avoid the problem. Anytime you want to add a Boolean, assume you're going to have to make it into an enumerated list up front.

Also, avoiding Booleans prevents your integrators from having to learn many new terms, especially if they're going to localize. It's one thing to learn a list of 50 or 60 words in your API, like "type" and "breed". Don't force them to learn all the English values, too. If your integrator is Spanish, he might not use "cat", he'll use "gato". So why should he have to learn that gato "isCat"? Minimize the number of tokens and avoid putting values in your action names.

And I don't even know what this means. If you can tell me ...

For the same reason you shouldn't embed values in actions, don't embed units. Document the units. Also, the units may change, and you don't want to have to change the action names.

Here we have the animal type. The animal name. Number of legs. Number of heads, I think, or maybe number of tails. This must be the hair color and the breed. Then height? Length?

Anyway, don't do this. There is no need to add the number of legs once you know the animal type. If beagles are generally brown, there is no need for the hair color by default.

Here we wrap the parameters in a hash, so the meaning of each field is clear and we can leave out the defaults.

Try not to use a global state. For one thing, it avoids race conditions. For another, the application now has to use business logic to figure out what state it's in, how long to wait, how often to poll for the answer, and so on. Send the result back with an event, or a socket, or an email, or what have you. Let the application be dumb.

When considering resources, you may have dozens of ID fields for your database, your UI, some other system. Don't expose them all to the integrator; only give him what he needs. Also, don't return one kind of ID from one command and then require a different ID for a different command. We want to let him cascade the output of one command into the next one. He shouldn't have to look around for the information he needs.

Like actions, don't use Boolean parameters and don't embed the values in the parameter names.

I've seen this kind of documentation. It's not helpful. Remember, your result is being sent to an application, not a person. The application has to take the result and figure out what to do next, and for that it needs the exact list to parse. If something returns an enumeration, link to the enumeration or provide all the possible values.

Enums are good. Pass the enum code, not the value. This way the integrator can localize the results. So don't pass literals. In the second example, the developer tried to be clever by avoiding literals but concatenating strings together, but that's not useful if the result is going to a different kind of UI or if the language reads right to left. Pass the code and the values and let a utility do the substitution.

Don't use literals even if you don't plan on passing them on to the user. You might enjoy parsing a literal return value, but it's dangerous. If your API returns error code 22, the next person working on the API isn't going to change the return code to 23 just because it's his birthday. So you can expect it to remain the same. On the other hand, if your application parses the return value "no dogs found", it's going to break when the API changes all references to "dog" to "BarkBuddies".

The last example was also a problem, because you may have several results to pass back, and now you have to worry about parameter order. Pass the values back in a structure and let the utility figure out how to handle it.

What do we need documented for values? The range or possible values for the value. The units. Whether there is a certain subset of range or options that is recommended, like 4 legs. The default value or option, of there is one. Any dependencies between the values, like if that is above 4 then this has to be below 3. And where the implementer can get the value; which API returns the list of options for this value, so they know how to string the APIs together.

Speaking of documentation. A big problem with a lot of documentation is the writer assumes you know everything about the product before you start. Lots of documents start with "Welcome to our system. To log in ...." That's not helpful. Take a paragraph to orient your reader by explaining what your system is, and what the user can expect to do with it. Like a mini-table of contents so they know what to look for and if it's worth reading.

Don't waste their time documenting basic concepts like classes and programming ideas. But don't assume they know what your terms or products are or do. Don't just say it's a system for managing BarkBuddies. Tell them that a BarkBuddy is a dog.

Hyperlink so that they can get more information, so you they don't have to read the same information more than once. A content generation system like doxygen, JavaDoc, Swagger, etc does this for you.

Provide examples. Some people can learn the system straight from the examples, and in fact you may be able to get what you need just by cut and pasting the examples. And include a complete list of error codes that might be sent back.

Here's a very common source of annoyance. I hate documenting delivery packages, because I should never have to. They should be self-explanatory. Also, unless the API is a web page, no R&D team ever knows how the API is delivered. Is it a zip file? A DVD? How does the user get it? R&D teams don't even know this the day before, or of, or after the delivery.

But the delivery is the very first thing that the user interacts with. Please make it nice and clean. Make all the file names and directory names self-evident. Don't include parse.h and also parseNew.h or parse2.h . Clean it up! Remove everything that is not needed: files, directories, methods, and so on. Don't make the integrator wade through all these things he doesn't need, because he WILL call support and try to figure out what to do with them. Include the localization files and anything he can customize, like enums and configuration files.

Last tips. Consider a quick start guide to get the user up and running. Consider a cookbook that the user can cut and paste. And, if it makes sense for your API, consider a wizard that will generate the code with everything already in place without errors. Just make sure the wizard is up to date with the latest code changes.

Thank you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)